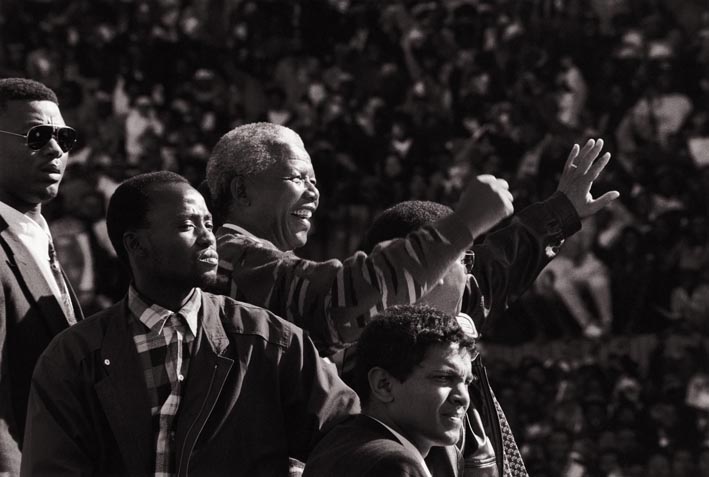

George Hallett is an author, book designer, and award winning photographer. In 1995, he won a Golden Eye Award for the following photograph.

In February 1994, Hallett dreamt that he lunched with Nelson Mandela. The idea of meeting Mandela was thrilling. Yet, he found one aspect troublesome. He recalls, “One disturbing thing about the dream was the fact that our chairs were all balanced on the hind legs. I went to Madame Keltum in Paris for an interpretation. She … proceeded to tell me that yes indeed, I would be meeting with Mandela and the reason why the chairs were balanced on their hind legs, was because of violent instability in the country.”

A few weeks after the dream, Hallett received a call from his friend Dr Pallo Jordan. The initial steps to the dream’s fulfilment began taking shape. Jordan, who served as South Africa’s Minister of Arts & Culture from 2004 to 2009, asked Hallett to return to South Africa and photograph the country’s first Democratic Elections. So, he departed Paris and returned home.

Hallett describes an early encounter. “Mandela was rehearsing for his first TV debate with then President De Klerk. … After an hour or so of hard work, Mandela asked for a break outside in the fresh air. I followed him outside. A woman came up to him with a phone and said it was President De Klerk. … He stands there and tells De Klerk that he should stop the violence as soon as possible because of the looming elections around the corner. ... A domestic worker with something in her hand approaches from behind. Frame and shoot. She does not see his face. He hands the phone back to the receptionist. Then peace is shattered with women shouting and running towards him. I lift my Leica M3 and manage to get the shot a split second before they touch him. Shortly after that we are inside again having lunch. The dream came true.”

When photographing Mandela, Hallett worked with two cameras, “one for close-ups of his face, another to get the surroundings.” He explains, “When photographing the positive aspects of humanity, it is important to include the social surroundings of people. Be that a street scene, an interior, a stage setting or a portrait.”

Hallett has photographed a wide array of people in a number of countries. Despite the vastness of his oeuvre, there is a connecting thread. In each photograph, he skilfully captures the humanity of his subjects.

He delights in photographing people without them being aware of his presence. He is the proverbial “fly on the wall”.

In addition to people, he has always been fascinated by architectural forms and textures. In some photographs, he combines being “the silent observer” with his love of structures.

Hallett says, “Coming from South Africa, I have learnt to be humble and generous with my dealings with people.” This leads to photographs that are pure. They are without judgment or staging. The viewer is presented with unadulterated humanity be it the hardships of life or moments of respite.

One such moment of rest is captured in one of Hallett’s favourite photographs, Farm workers. He states, “My grandparents ended up on this farm after being evicted from their house in the fishing village of Hout Bay by the Apartheid regime because the village became a Whites only residential area. I went to visit them one Saturday and as I walked up the path I saw the farm workers sitting under the oaks having a break. On the right were a loving couple. The man with the beard was Italian and he took care of the vineyards. His girlfriend went to junior school with me. The relationship was illegal and they could not care a s..t about that. I waved and focussed my Mamiya 6x6cm camera on them, thus capturing a rare moment of a loving and caring group of workers that no one even bothers to acknowledge.”

A couple years later, District Six became the target of the Apartheid regime. As a newly declared Whites only area, over 60,000 people were forced to leave their homes. Encouraged by two friends, the poet James Matthews and artist Peter Clarke, Hallett began recording the life of this community before the bulldozers arrived.

While engaged on this project, he was introduced to The Sweet Flypaper of Life, a collaborative work by Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes. In this book, DeCarava and Hughes explore life within Harlem through photography. Using this as inspiration, Hallett photographed writers, artists, actors, dancers, and musicians. He displayed these photographs in a solo exhibition at the Artists Gallery in Cape Town.

Reflecting on that period, Hallett notes, “As my political insights became more mature, it also became apparent to me that it was time to leave my not so beloved country.” Soon after his first exhibition, he departed South Africa for England.

Once in London, Hallett’s artistic skills expanded. He refers to the streets of London as his university. Through Isaiah Stein, a fellow South African exile, he was introduced to James Curry at Heinemann African Writers Publishers. This meeting led to him designing photographic book covers. He then presented his portfolio to the Times Educational Supplement in Fleet Street. Hallett ended up working with the Times for several years doing spreads and covers on a variety of subjects including “education, the Afro-Asian community, Gypsies, Hippies, Coal miners, youth and many other subjects of fascination.”

While living abroad, Hallett’s social circle included many South African exiles. He recalls, “I went to listen to our Jazz musicians at the 100 Club in Oxford Street on Monday nights. There I met more South Africans. The 100 Club was home away from home for us. I immediately began taking pictures of the musicians on stage as well as at home, relaxing with friends and family members.”

Hallett’s first European exhibition was in Paris in 1971. It was a group show with South Africans Gerard Sekoto and Louis Maurice. Shortly after, he had a solo exhibition in the Westerkerk in Amsterdam organized by the World Council of Churches. He remembers this exhibition as “a glorious occasion.” He remarks that this was the first and last time he experienced such a wondrous vernissage. Both exhibitions focused on his South African work and presented “a positive image of Black people living under the indignities of Apartheid.”

Hallett stresses that many individuals helped him evolve into the photographer he is today. This evolution began shortly after his graduation from high school. He remembers often critiquing the works

of photographer and friend Clarence Coulson. One day, Coulson tired of the comments and shouted ‘If you know so much about photography, why don't you go out there and take your own photos.’ This was something Hallett longed to do but without a camera or the means to purchase one, it seemed improbable.

Coulson sent Hallett to Mr. Halim, the owner of Palm Tree Studio in District Six. Halim gave him an old Leica and instructions on its use. The burgeoning photographer was tasked “into the streets of the Cape Peninsula to photograph whatever [he] wanted.” This experience proved invaluable. Hallett was exposed to different groups of people and learned to negotiate within diverse situations. Despite the difficulties of living under an Apartheid regime, people maintained their humanity. He witnessed acts of kindness in various situations.

Throughout the years, Hallett has created an impressive body of work. He states, “Using my District Six experiences, I was able to always get exclusive shots that the other photographers never thought possible.”